Boeuf a la Ficelle

Recipes tell us more than simply how to cook. They they also tell us something about the people who are writing them and the people they assume are going to be doing the cooking. Without getting all French deconstructionist and everything, a recipe is more than just a set of instructions.

This is especially obvious if you compare the recipes of today’s popular cookbooks with those from a couple of hundred years ago. Let’s just pull a couple from the shelf more or less at random.

In Hanna Glasse’s “The Art of Cookery,” published in 1776, you find this recipe for salmon pie: “Make a good crust, cleanse a piece of salmon well, season it with salt, mace, and nutmeg, lay a piece of butter at the bottom of the dish and lay your salmon in. Melt butter according to your pie; take a lobster, boil it, pick out all the flesh, chop it small, bruise the body, mix it well with the butter, which must be very good; pour it over your salmon, put on the lid, and bake it well.”

Another old favorite is Lettice Bryan’s “The Kentucky Housewife” (1839). Her instructions for baking “a hind quarter of shoat” begin: “Prepare it as for roasting . . .”

Well, you get the picture. The first thing that strikes you is what the recipes leave out: things like quantities, what “a good crust” might be or maybe how you roast a shoat to begin with. The authors of those recipes--brilliant cooks, no doubt--assumed that most of the people who would be reading them would be similarly accomplished.

That wouldn’t do today. Not by a long shot. Every year we find people coming into the kitchen with less and less cooking knowledge. Recipe writers need to spell out, in as much detail as possible, everything that goes into the preparation of a dish--from shopping for the ingredients to how to fit it into a menu.

Beyond that, as people have less confidence in their abilities, one of our roles must be to reassure them that they can do this. Moreover, it’ll be fun!

All of that is a long-winded way of saying the Times Food section is changing the way we write our recipes. There is nothing earth-shaking, just a few improvements we think will make the recipes easier to follow and provide an extra measure of assurance.

In fact, you may not have noticed these changes at all if we had not drawn your attention to them. For one, from now on we’ll be letting you know at the appropriate time if you should be heating the oven, greasing a pan or doing something else like that, rather than surprising you with it later on.

And we’ll begin using articles in recipe instructions. No more “chop carrots”; it will be “chop the carrots.” The difference is small but important: Writing in that abbreviated telegraphic style reinforces the idea that recipes are codes breakable only by members of a select club.

With all the trouble we take to test every recipe that runs in the Food section and make sure every detail is worked out, that’s not at all the message we want to send.

Furthermore, we’re going to work harder to take advantage of everything our kitchen discovers during testing these recipes--tips and tricks that make cooking easier.

All of this is nothing new. The other day I came across this recipe for Boeuf a la Ficelle in Edouard de Pomiane’s 1930s classic “Cooking With Pomiane” (it’s part of a new collection of classic cookbook reprints by Modern Library that will begin hitting stores in February).

BOEUF A LA FICELLE

To make this dish all you need is a piece of top rump steak weighing between 1 1/2 and 2 pounds, a large saucepan of well-salted water boiling on the fire and a piece of string.

Get the butcher to give you a piece of rump steak as nearly cube-shaped as possible and to tie it securely in shape.

Now fix a piece of string to the meat. Lift it up, and the meat swings slowly on its string like an incense burner. Look at your watch and take careful note of the time. Plunge the meat into the saucepan and tie the string to the handle in such a way that the meat is suspended in the water without touching the bottom. Put on the lid and wait. The water will have gone off the boil for a moment, but as the heat is intense it soon boils once more.

But, you will say, surely this is not the way to make a stew? You are quite right, but you are making boeuf a la ficelle. When you make a stew you want the meat to be edible whilst the gravy is rich and savory. For this reason you put the meat into cold water and raise the temperature very slowly so that after long, slow cooking the goodness is drawn out of the meat.

But now you are in a hurry and you want to prepare the meat so that it conserves all its juices. For this reason, you must seal it by plunging it straight into boiling, salted water. You must allow 15 minutes’ cooking time for every pound of meat, so look at your watch carefully.

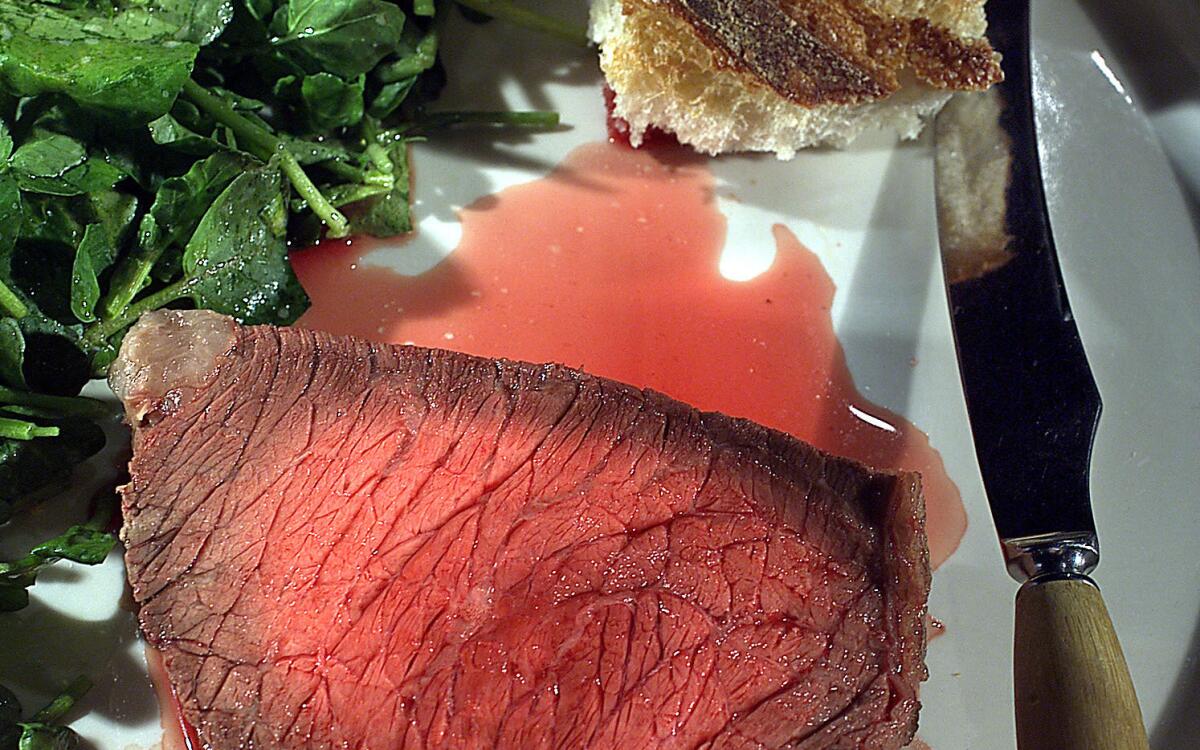

When the meat is almost ready, prepare a hot dish and some watercress and see that your salt mill is ready on the table. Lift the beef from the saucepan and remove the string. The meat is gray outside and not very appetising. At this moment, you may feel a little depressed. But don’t worry. Take a very sharp knife and slice into the beef. Inside, it is rosy and tender and the gravy pours into your plate. No roast could be quite like this.

Give each of your guests a thick slice of meat, some watercress and a piece of French bread. A couple of turns with the salt mill and you are ready to eat.

Now that’s how you write a recipe! I was so hungry by the end of it that I couldn’t wait to try it at home. When I did, I found it worked exactly as advertised. When I pulled it from the pot, my wife took one look at that gray hunk of meat and blanched (we were having friends of hers over for dinner). But when I sliced it open, the meat was perfectly rosy all the way through, dripping with juice and with the most perfect beefy flavor.

Of course, I couldn’t resist making a few alterations. While my version may lack the charm of de Pomiane’s, it does include a little more specific information. These days, detail trumps poetry.

Measure the depth of a large pot by tying a length of string around the roast and then suspending the roast inside the pot so that the roast doesn’t touch the bottom. Lay a wooden spoon across the top of the pot like a bridge. Tie the string to the spoon. With the meat still suspended, fill the pot with enough water to submerge the roast.

Remove the meat and the spoon, cover the pot tightly with a lid and bring the water to a rolling boil over high heat. Add 2 tablespoons of salt and carefully lower the beef into the water so it hangs from the spoon, not touching the bottom. Prop the lid on top until the water returns to the boil, then remove the lid. Cook the beef 15 minutes per pound for a center that is on the cool side of medium rare, 20 minutes per pound for medium.

When the meat is done, remove it and the spoon from the boiling water, cut loose the suspending string, cover the roast loosely with foil and set aside for 10 to 15 minutes.

While the beef is resting, trim the tough stems from the watercress and place it in a salad bowl. In a small mixing bowl, beat the vinegar into the mustard, then gradually add the oil, beating with a fork to make a smooth dressing. Season to taste with a little salt. Pour it over the watercress and toss well.

Cut free the strings that bind the roast and carve the meat into 1/4-inch slices, being careful to reserve all meat juices. Arrange the slices in the center of a warm oval platter. Arrange the watercress salad around the outside of the roast, and then the bread slices on top of that.

Serve immediately, passing the very coarse salt at the same time to sprinkle on the meat according to taste. Use the bread to sop up as much of the meat juice as possible.

Get our Cooking newsletter.

Your roundup of inspiring recipes and kitchen tricks.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.