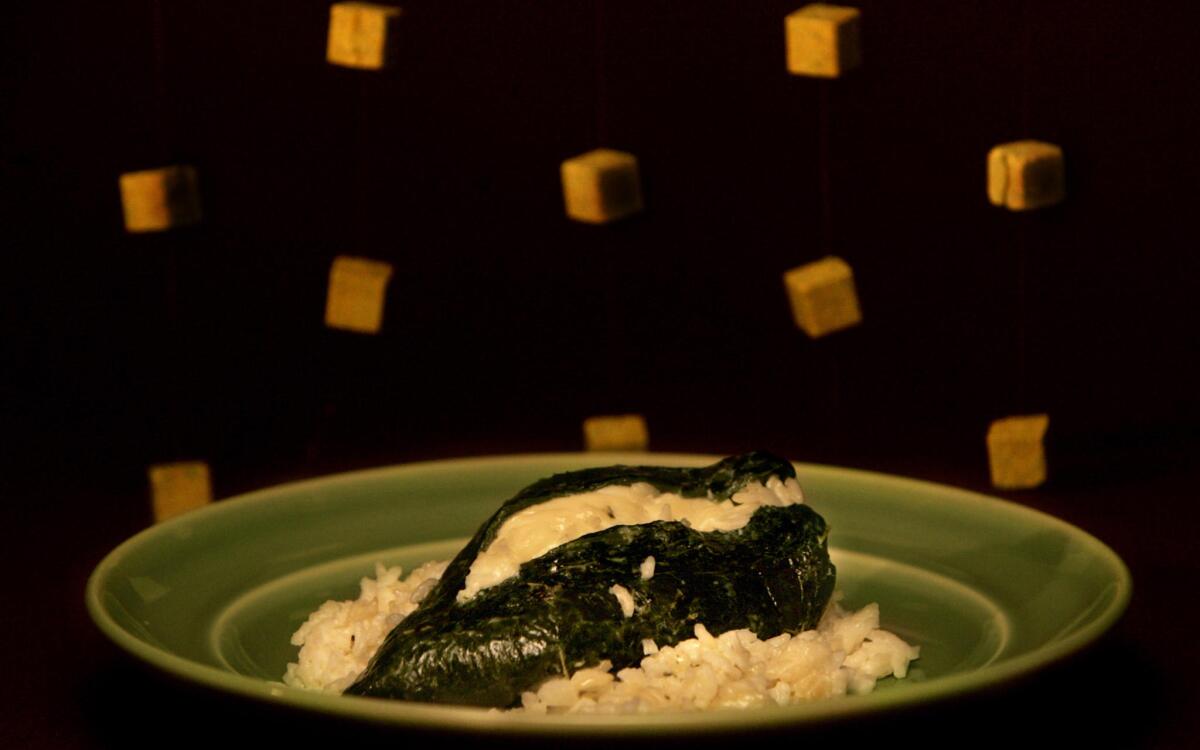

Chiles rellenos de queso (chiles stuffed with panela cheese)

A few years back, I went to Mexico City to learn to cook at the apron strings of my step-grandmother, Josefina Figueras viuda de (widow of) Carreno. Josefina is one of those women -- you’ll find them anywhere in the world where home cooking has not been superseded by “home meal replacement” -- who shuffles into the kitchen at dawn and stays there until well after she’s served her family dinner. Throughout the day, she busies herself toasting dried peppers, charring fresh ones, mashing various ingredients in a molcajete and blending others into chile powders and pastes.

On this particular day, we’d spent the better part of the morning roasting, peeling and stuffing poblano peppers, preparing a special-occasion dish traditional to my late grandfather’s San Luis Potosi. The cheese-filled chiles would be floated and cooked in a large pot of rice boiled in milk, and it was into that milk that, with the deft nonchalance of a person who spends 12 or more hours a day in the kitchen, she (plop!) tossed a chicken bouillon cube.

Naturally, I was horrified. I come from a generation of American cooks who have had it pounded into them from every serious cookbook that in any recipe calling for stock, canned broth is a poor substitute for homemade (a handy cross-referenced recipe calling for 10 or more ingredients is provided). Bouillon cube? Perish the thought. I once dated a guy who was the sous-chef at Lutece (which was considered the finest French restaurant in New York at the time), whose idea of a shortcut to homemade meant stopping by Second Avenue Deli and buying its famous chicken broth.

As I spent more time with Josefina, I saw her toss bouillon cubes into rice dishes (plop), caldos (plop), beans (plop) and complex, labor-intensive moles and chile sauces (plop, plop).

Il dado in the pot

A few years later, I was dispatched to the mountains of Sicily to co-write a cookbook for Giovanna and Wanda Tornabene, who run a restaurant out of the 14th century abbey that is their home. The abbey is surrounded by groves of nut and olive trees whose fruits were used in our cooking. We made daily trips to town to buy fresh-baked bread and ricotta cheese made that morning from sheep’s milk. And we had a helper named Peppe whose job was to shell fava beans and pick herbs when we needed them, and to gather mushrooms after a rain and wild fennel from the mountainsides during its short season.

Nevertheless, on my first day in that kitchen I spotted -- right there on the shelf with the salt-packed capers, anchovies and olive oil pressed from olives grown on the premises -- a plastic box housing those familiar foil-wrapped cubes. It was a veritable arsenal of bouillon cubes, including beef, veal, chicken, vegetable and fish.

I spent my entire trip trying to convince the Sicilian ladies that the bouillon cube -- known to them as il dado, “the cube” or “the dice” -- was not an acceptable compromise. When I returned home, Colman Andrews, editor of Saveur, the magazine devoted to “authentic cuisine,” asked me how it went.

“I loved the food overall,” I told him. And I wasn’t sure I’d be able to live without the sausages and ricotta of the region, but, errr ... “They use bouillon cubes.”

I expected him to react with the kind of horror and confusion I’d felt when I saw Josefina drop that first cube.

“Yeah,” he said, dismissing the comment. “Marcella throws them in everything.”

He was referring to Marcella Hazan, America’s foremost authority on Italian food. Throughout her cookbooks, she not only suggests bouillon cubes as an alternative to homemade broth, she even also calls for them specifically in certain recipes.

The irony, of course, is that in this type of traditional cooking, which has never been more fashionable (think “slow”), the very cooks we are emulating have no qualms about dropping the cube. In fact, using bouillon cubes is de rigueur for home cooks all over Europe, including France, where canned broth is simply not available in most supermarches. Organic free-range chicken broth in a box? Forget about it. And it’s not just home cooks in Europe using them. French chefs right here in L.A. plop bouillon with the best of ‘em.

“This is 2005,” says Eric Scuiller, executive chef at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Scuiller may have five caldrons of stock boiling at any given time in the hotel kitchen. But at home, “Who has time to roast bones, make a bouquet and reduce a stock for three hours?” The bouillon cube, he says, is a nice alternative. “My mother uses it.”

Chefs’ secret

AT the regional French restaurant Mimosa in Los Angeles, chef Jean-Pierre Bosc uses a small amount of chicken bouillon to boost the flavor of his homemade broth. And at Mille Fleurs in Rancho Santa Fe, chef Martin Woesle uses “chicken base,” a professional Knorr product, as a starter for homemade broth, and also to flavor the water he uses to cook rice, pearl pasta (Israeli couscous) and to braise the vegetables he buys on his daily trips down the hill to Chino Ranch.

Though nothing would seem farther from the spirit of Alice Waters, Alan Tangren, who was the forager at Chez Panisse for many years and also worked closely with Waters on three of her cookbooks, admits to using bouillon cubes at home. It’s just the thing when he wants to add “a little complexity of flavor” to a sauce or stock, or to give a “boost” to a homemade stock or slow-cooked dishes like coq au vin and beef stew.

But the Tornabenes, Hazan, my step-grandmother Josefina and others have gone beyond simple stock substitution and use it as an ingredient valued for its sake. The cube has become a sort of seasoning, showing up in dishes where broth might not normally be present.

Hazan stirs a beef bouillon cube into a simple butter sauce inspired by the drippings of roasted meat in a recipe for pasta with butter and rosemary sauce in “Essentials of Italian Cooking.” Josefina often reaches for bouillon cubes, she says, when she needs salt. In Sicily, I watched as the Tornabenes carefully selected a cube from the different flavors, then crushed and stirred a chicken bouillon cube into a frying pan with stewing peppers or added a vegetable bouillon cube to water for poaching fish. Depending on the dish they were making, they tossed different kinds of cubes into pasta water to allow the flavor to penetrate the pasta.

One Sunday afternoon, after four of us had spent some 20 collective hours making ravioli filled with delicate sheep’s milk ricotta -- a family triumph -- we boiled those little bundles in a pot into which -- plop, plop, plop, plop, plop -- yes, five veal bouillon cubes had been dropped. Not only was the “veal flavor” meant to penetrate our handmade pasta, but the pasta water itself would be mixed with equal parts butter, and that alone would dress the pasta. Despite my anti-bouillon bias, I had to admit, the subtle sauce was perfectly delicious and just what the ravioli called for.

At least one L.A. French chef also uses cubes to enhance pasta. Although he wouldn’t use them at Bastide, chef Ludovic Lefebvre says that when he’s at home, “I love to put it in the pasta water when I boil the pasta.” He also uses it to boost the flavor of soups. “It’s just a reflex you get in France,” he says. “I’ve seen my mom use it, my grandmother.... It’s good, no?”

Roast the chiles over the flame of your stovetop until they are black. Put them in a plastic bag and cover the bag with a warm, wet towel to steam the chiles. Let stand 10 to 15 minutes. Peel off the skins. Remove the veins and seeds very carefully, making just one cut from the stem end midway (or less) down the chile. Rinse the chiles under running water, as briefly as possible, to remove the skins.

Cut the cheese into small logs that can be easily tucked into the chiles. Stuff the prepared chiles with the cheese as full as you can while still able to close them.

Place the oil in a big soup pot that you can serve the dish in. Add the rice and fry it for about 6 minutes, until it does not stick to the pan but slides around very easily. The rice will get only the very slightest bit of color.

Add the milk and bouillon cube to the rice and bring it to a boil, stirring to dissolve the bouillon cube. Cook for about 7 to 8 minutes, then, as the rice begins to thicken, use a slotted spoon to add the prepared chiles. (This is tricky. If you don’t cook the rice enough, the chiles will swim around in the pot and may sink to the bottom, and you’ll likely lose the cheese. But if you cook the rice for too long, it will become so thick that when you plop the chiles in, they’ll just rest on top. You want the chiles floating in the rice, so that the rice almost completely covers them with a little green showing but they are not sitting on the bottom of the pot.)

Continue to cook the chiles and rice, uncovered, until the rice is tender. Taste the rice occasionally. If you find it is not tender but you’re running out of liquid, add a little more milk and cover the pot.

Serve immediately (it’s impossible to reheat). Scoop into the rice, lifting out the chiles so that each person gets a whole chile and some of the surrounding rice.

Get our Cooking newsletter.

Your roundup of inspiring recipes and kitchen tricks.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.