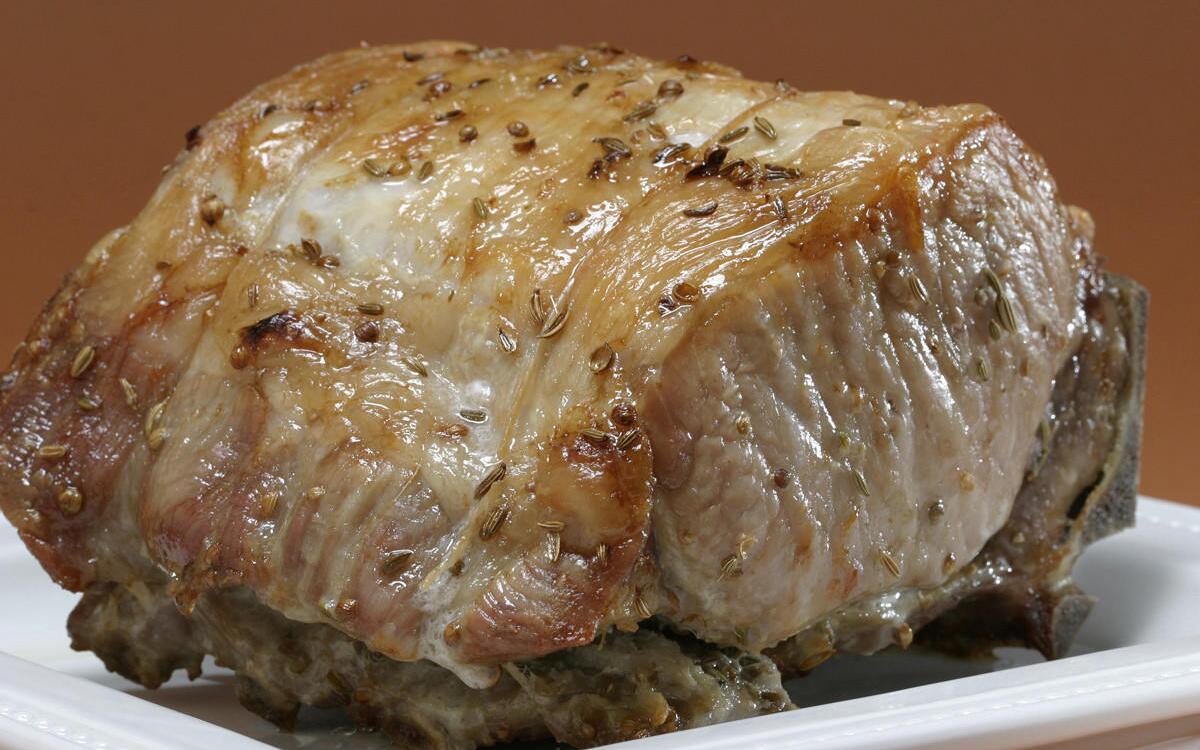

Standing rib roast of pork

There’s a lot of inspiring stuff flying off the presses lately, and we’re thrilled to make room on our bookshelves -- but not at the expense of that one old favorite. You know, the cookbook whose jacket has gone missing, whose pages are stained with gravy, whose splitting spine is taped together. It’s the one we can always count on for great ideas and practical advice. In that spirit, here are the all-time favorite cookbooks of Times Food staff writers:

*

Russ Parsons, columnist

Want to know why Richard Olney’s “Simple French Food” is my favorite cookbook? Read the recipes -- the one for onion panade, for example. In fact, just read the first sentence: “Cook the onions, lightly salted, in the butter over a very low heat, stirring occasionally, for about 1 hour, keeping them covered for the first 40 minutes.”

In that one brief passage, we get three cooking lessons: Salt the onions from the start to help draw out the moisture so the onions wilt faster. Start them in a cold pan so they melt without scorching. And cover the pan early on to trap the heat, helping retain moisture and keeping the onions from browning.

Even better, the dish is a total knockout. It’s like a transcendent French onion soup -- deeply aromatic, nearly custardy, with a stunning gratineed cap. All this comes from only the humblest ingredients. No fancy foodstuffs, no expensive equipment and no tricky techniques. With Olney’s cuisine, time and care are all that are required to work miracles. There is no more important lesson for a cook to learn than that.

*

Donna Deane,

Test Kitchen director

I love poring over cookbooks, but in truth, I rarely follow a recipe to the letter when I’m cooking at home. Unless, that is, it’s from Julia Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking” (co-written with Louisette Bertholle and Simone Beck). I first opened this book in the early 1970s, and it hasn’t let me down since. The instructions are clear and thorough, the simple line drawings extremely helpful in illustrating cooking tips. Even what might seem like a fancy dish (a charlotte, say) feels doable. One of my all-time favorites is the blender hollandaise sauce; it’s so deliciously foolproof, you can’t help but feel confident that you’re really mastering the art.

*

S. Irene Virbila,

restaurant critic

Judy Rodgers is a consummate chef, and “The Zuni Cafe Cookbook” reflects the sensibility behind the intelligent and sensual food at her long-running restaurant in San Francisco.

The writing is wonderful, the selection of recipes smashing. I get hungry just thumbing through it. I’ve cooked from it so much that the pages just naturally fall open at certain recipes, such as the peach crostata, the world’s greatest roast chicken with Tuscan bread salad, or, standing rib roast of pork. The pork has become my fallback for entertaining when I don’t want to spend the whole day in the kitchen. It’s incredibly easy and incredibly satisfying, and a great dish for a beautiful Chianti or Sangiovese.

*

Barbara Hansen, staff writer

On my first trip to Mexico a couple of decades ago, I discovered a bilingual book that became my bible to Mexican food. “Mexican Cook Book Devoted to American Homes,” by Josefina Velazquez de Leon, first came out in 1956, but nearly half a century (and many reprints) later, it remains a valuable guide.

Velazquez de Leon, the Mexican equivalent of Fannie Farmer, provides practical cooking instructions but also makes her country’s vibrant cuisine come to life. Leafing through the pages, I can practically taste the mole de olla (a fragrant and spicy beef stew and stuffed squash blossoms as they would have been prepared in a traditional kitchen, where clay pots simmer over a wood fire.

*

Charles Perry, staff writer

In 1968, I was a romantic in the kitchen. All ingredients taste great, I figured, so you could just mix and match. Whee! Some would call this California cuisine before its time. Back then, I thought of French food as a lot of bland, pretentious fripperies. But one night, an old college friend cooked cotelettes de porc au cidre from Elizabeth David’s “French Country Cooking,” and I was awestruck. The unexpected combination -- of browned pork, rosemary, cider, garlic and capers -- really worked.

There was nothing improvisational about it. The dish was as perfect as a Doric column -- despite David’s disdain for giving exact measurements. Today I have hundreds of cookbooks from around the world, but I still find myself going back to David’s rock-solid recipes.

*

Leslie Brenner, Food editor

Pastry making is not my forte, nor do I have a sweet tooth. That’s why when Lindsey Remolif Shere’s “Chez Panisse Desserts” was published in 1985, I flipped over it. Shere was Chez Panisse’s first pastry chef, and a thread of sophistication runs through her desserts, which are more about flavor than they are about sugar. No one can look into the soul of a fruit the way Shere can: She has an innate sense of what to do with a tangerine (use it to flavor oeufs a la neige). She even coaxes flavor out of cherry or apricot pits to make noyau ice cream. And she pairs figs dipped in caramel with anise or Chartreuse creams. “The herbal flavors complement perfectly the sweet muskiness of the fig,” she writes. What could be more inspired than using Chartreuse (or Calvados or Bourbon or late-harvest Riesling) to finish a meal with an elegant, easy flourish?

Place the roast, bone side up, on a cutting board and locate the rubbery seams between the vertebrae. Crack through each one by easing the blade of a heavy cleaver or the bolster of a heavy chef’s knife into each joint and then tapping firmly with a rubber mallet (or a hammer wrapped in a towel). It may take a few taps to go all the way through the seam and joint, but take care not to cut deeply into the meat itself. The blade of your knife ought to sink no more than 1 1/2 inches into the seam.

Flip the roast over and trim away all but 1/4 -inch-thick layer of fat. Begin boning the loin, starting with the thin layer of meat and fat near the end of the rib bones. Resting the tip of your knife flat against the curved rack of bones, make a series of smooth cuts between the loin and bones until you reach the “elbow” of each rib bone. Leave the loin attached to the other angle of the “elbow,” so you can open and close the roast like a book.

Season the whole roast, including the rack of bones, literally inside and out with salt (we use about 1 tablespoon sea salt for 3 pounds of roast); target the thickest sections most heavily, and the two end faces of the loin most lightly. Roughly chop the garlic, then crush in a mortar. Smear on the inside face of the loin. Slightly crush the fennel and coriander seeds. Scatter about two-thirds of them on the inside of the loin and the facing bones, then close the loin back up and sprinkle the remainder evenly over all of the other surfaces.

Truss the roast, looping and knotting a string between every two ribs. Cover loosely and refrigerate. (Remove the pork from the refrigerator about 3 hours before roasting.)

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees.

I usually take the temperature of the roast just before cooking it, looking for 50 degrees at the center of the thickest section. Stand the roast in a shallow roasting pan or in a heavy rimmed baking sheet not much larger than the meat. Place in the center of the oven. For a juicy roast that is cooked through, but with a faintly rosy cast, roast to 135 degrees. (If the eye of your roast is smaller than 4 inches across, cook it to about 140 degrees; it will stop cooking more abruptly when you remove it from the oven.) Start taking its temperature at about 45 minutes, and allow between 1 and 1 1/2 hours for a 4-pound roast. Turn the roast or adjust rack height if it is browning very unevenly.

Set the roast on a platter, tent loosely with foil and leave to rest in a warm, protected spot for about 20 minutes, then take the temperature again. Like any roast, it will continue to cook as it rests, but the rack of bones retains heat particularly well, so the temperature should climb to about 160 degrees. The meat will be cooked through but still moist.

Pour any fat from the roasting pan, then moisten it with the pork stock, the chicken stock or the water and wine, to capture any fallen aromatics and deglaze the baked-on meat drippings. Pour into a small saucepan and simmer until the sauce has a good flavor. Add any juice from the pork platter. Alternatively, for a more lavish sauce, simply heat up reduced pork stock.

The rib roast is easy to serve; just carve between the rib bones, then break into chops. Snip the trussing strings as you go. Alternatively, you can remove all of the strings, bone the loin and slice into medallions. Then break the rack into crusty ribs to eat with your fingers.

Get our Cooking newsletter.

Your roundup of inspiring recipes and kitchen tricks.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.